Photograph of Hayao Miyazaki, smiling

Enraged by the greed and ugliness of modern life, Hayao Miyazaki has devoted himself to making the most innocent and beautiful children's films imaginable. In a rare interview, Japan's answer to Walt Disney tells Margaret Talbot why you shouldn't buy his DVDs, and why Tokyo deserves to be buried underwater.

The building that houses the Ghibli Museum would be unusual anywhere, but in greater Tokyo, where architectural exuberance usually takes an angular, modernist form – black glass cubes, busy geometries of neon – it is particularly so. Outside, the museum resembles an oversized adobe house, with slightly melted edges; its exterior walls are painted shades of pink, green and yellow. Inside, the museum looks like a child's fantasy of Old Europe submitted to a rigorous Arts and Crafts sensibility. The floors are dark wood; stained-glass windows cast candy-coloured light on whitewashed walls; a spiral stairway climbs – inside what looks like a giant Victorian birdcage – to a rooftop garden of wild grasses, over which a robot soldier stands guard.

Situated in a park on the outskirts of Tokyo, the Ghibli Museum is dedicated to the work of Hayao Miyazaki, the best loved director in Japan today, and – especially since his film Spirited Awaywon the Oscar for Best Animated Film in 2003 – perhaps the most admired animation director in the world. Miyazaki's zeal for craft and beauty has set a new standard for animated films. He not only draws characters and storyboards for his films; he also writes the rich, strange screenplays, which blend Japanese mythology with modern psychological realism. He is, in short, an auteur of children's entertainment, perhaps the world's first.

Miyazaki designed the Ghibli Museum himself. The museum was partly funded by his film studio – after which it is named – and is now a hugely popular attraction. Though it is intended for children, who might be supposed not to care so much for beauty per se, it is, in nearly every detail, beautiful. The museum showcases not only the visual splendour of Miyazaki's films, but also what inspires them: among other things, a sense of wonder about the natural world; a fascination with flight; a curiosity about miniature or hidden realms.

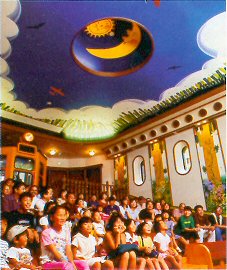

Miyazaki is detail-oriented to the point of obsession – he travelled to Portugal to look at a painting by Hieronymus Bosch that had long haunted him, and sent his colour designer to Alsace to scout hues for his latest film, Howl's Moving Castle (released here later this year) – and so, too, is his museum. For the in-house theatre, which shows the short films he makes for the museum, he hired an acoustic designer to create an uncommonly gentle sound system. Miyazaki wanted the opposite of the 'tendency in recent Hollywood films', which is 'to use heavy bass to try to pull the audience in.' He thinks cinemas can be claustrophobic, even overwhelming places for children, so he wanted his cinema to have windows that let in natural light, bench-style seats that a child can't sink into, and films that make them 'sigh in relaxation.'

Some of Miyazaki's ideas could not be realised. He has wanted to make a mountain of dirt at the Ghibli Museum, with muddy, slippery stretches where children 'would fall and be scolded by their mothers.' He had liked the idea, too, of a spiral staircase that gently swayed when you walked up it. These notions were eventually deemed unsafe or impractical but, overall, the museum still feels stubbornly and joyfully idiosyncratic.

Despite Miyazaki's fame – Howl's Moving Castle grossed a record GBP 8 million in its first week in Japan – he almost never grants interviews. Yet a few days after I visited the museum, I was lucky enough to run into him during a tour of his studio, and he chatted amiably. It immediately became apparent why he is compelled to create imaginary worlds. A spry, slim man of 64, with silver hair, parenthesis-shaped dimples and thick, expressive black eyebrows, Miyazaki betrayed a profound dissatisfaction with modern life. He complained, 'Everything is so thin and shallow and fake.' Only half in jest, he said that he was hoping for the day when 'developers go bankrupt, Japan gets poorer, and wild grasses take over.' And the conversation grew only darker from there. A man disappointed, even infuriated, by the ugliness surrounding him, Miyazaki is devoted to making whatever he can control – a museum, each frame of a film – as gorgeous as it can be.

John Lasseter, the director ofToy Story (1995) and A Bug's Life (1998), is an ardent fan, and friend, of Miyazaki. He recently visited the Ghibli Museum with his sons. 'You know how when you're watching a movie you'll say, "Wow, I've never seen that before"? With his films that happens in every sequence,' Lasseter said. 'He has such a big heart, his characters and worlds are so rich. The museum is a place to visit those worlds. It's like when Disneyland opened in the 1950s – visitors felt, in a very pure way, like they had walked inside a Disney film.'

People have been invoking Miyazaki and Disney in the same breath for a while, and in some ways the comparison is apt. Miyazaki films are as popular in Japan as Disney's are in America. (Spirited Away is Japan's highest-grossing film.) And like Walt Disney, Hayao Miyazaki started his professional career drawing animation cels and rose to head an independent cartoon empire with a tentacular hold on children's imaginations.

Yet in themes and style Miyazaki's eight films do not much resemble the Disney oeuvre. His is not a black-and-white moral universe: he has sympathy for the vain and the gluttonous and the misguided, a bemused tolerance for the poor creatures we all are. In My Neighbour Totoro (1988), one of the loveliest children's films ever made, two sisters, Mei and Satsuki, are not idealised: they are at once goofy, brave and vulnerable, like a lot of kids. The sisters have just moved with their father to a new house in rural Japan. Gradually the two girls discover a host of strange but benign woodland creatures. Unlike the animals in most American cartoons, these creatures are not excessively anthropomorphised; they don't speak, which somehow makes them seem both more plausible and more dignified, and which gives the girls the delightful challenge of interpreting them. In fact the film is focused on dignifying the girls' imaginations, honouring their ability to partake in a fantasy that is both comforting and fortifying – for we gradually learn that they are separated from their mother, who is ill in hospital.

Toshio Suzuki, a wry, articulate man with close-cropped, silver hair and an elfin grin, is Miyazaki's producer and long-time collaborator. 'When silents moved to talkies, Chaplin held out the longest,' he told me. 'When black and white went to colour, Kurosawa held out the longest. Miyazaki feels he should be the one to hold out the longest when it comes to computer animation.'

Miyazaki's starting point, Suzuki said, is often a small visual detail. When Miyazaki read a Japanese translation of the book Howl's Moving Castle, by the English children's author Diana Wynne Jones, he was immediately taken with the idea of a castle that moves around the countryside. 'The book never explains how it moves and that triggered his imagination,' Suzuki recalled. 'He wanted to solve that problem. It must have legs and he was obsessed with settling this question. Would they be Japanese warrior legs? Human-type feet? One day, he suddenly said, "Let's go with chicken feet!" That was, for him, the breakthrough.'

As with fantasy writers in the English tradition, from CS Lewis to JK Rowling, Miyazaki makes the details of the worlds he creates concrete and coherent so that we might better suspend our disbelief for the big leaps of fantasy. Miyazaki can be steely in pursuit of this goal. In a Japanese television documentary about Spirited Away he is shown at a meeting with his staff explaining how they are to draw certain images based on his story boards. 'The dragon is supposed to fall from the airvent but, being a dragon, it doesn't land on the ground,' Miyazaki says. 'It attaches itself to the wall, like a gecko. And then – oww! – it falls – thud! It should fall like a serpent. Have you ever seen a snake fall out of a tree?' He looks around at the animators, most of whom appear to be in their twenties and early thirties. They are taking notes, looking grave; no one has seen a snake fall out of a tree.

When he describes a scene in which his heroine, Chihiro, forces open the dragon's mouth to give it medicine, he says the animators should think of what it's like to feed a dog a pill. There is more note-taking but no sign this might be a familiar experience. 'Any of you ever had a dog?' Miyazaki asks. 'I had a cat,' someone volunteers. 'This is pathetic,' Miyazaki says. The documentary shows the chastened staff making a trip to a veterinary hospital, videotaping a golden retriever's gums and teeth, then returning to the studio to study the video.

Miyazaki doesn't care for a lot of contemporary Japanese animation. He is a leftist who thinks that too many people are making money out of children, who frets over the spectre of virtual reality 'eating into our emotional life', and who wishes we could drastically reduce the number of video games and DVDs available. He worries that he is contributing to the problem by making these films himself, and isn't keen on promoting them, which is one reason he resists interviews. Several people who know Miyazaki told me that mothers frequently approach him to tell him that their child watches one of his films every day, and he always acts horrified. 'Don't do that!' he will say. 'Let them see it once a year, at most!'

Hayao Miyazaki was born in Tokyo in 1941. His father helped run a family-owned factory that made parts for military aeroplanes. His mother, like the mother in Totoro, was sickly and often bedridden. At Gakushuin University in Tokyo Miyazaki studied economics and political science. But he also joined a children's literature group, where members read and discussed fantasy fiction.

In 1963 Miyazaki went to work as a rookie animator at Toei Animation, in Tokyo ,which primarily made cartoons for television. There he met Akemi Ota, an animator, whom he married in 1965, and who decided to stay at home when their sons were young. (Goro, who was a landscape designer before becoming curator of the Ghibli Museum, was born in 1967; Keisuke, an artist who makes intricate wood engravings, was born two years later.) On his first job at Toei, Miyazaki also met Isao Takahata, an animation director with an intellectual bent; and Michiyo Yasuda, the gifted colour designer, who went on to work on most of his films.

Children watching a Miyazaki film at the Ghibli Museum in Tokyo

Miyazaki is a workaholic, and that tendency was in full force by then. 'When I was small,' his son Goro recalled, 'he would come home at 2am and get up at 8am and do television series all year round. 'It was very rare for me to see him.' When, in his early thirties, Goro started working closely with his father for the first time, on the Ghibli Museum, he felt he 'understood his creative processes so well precisely because he'd been such an absent father. When I was a child I studied him. I watched his movies obsessively. I read everything written about him. I studied his drawings.' With a rueful chuckle, he added, 'I think that I am the number-one expert on Hayao Miyazaki.'

Toshio Suzuki met Miyazaki in 1978, when Suzuki was working as the editor of Animage magazine. He had been assigned to interview Miyazaki, but Miyazaki refused. 'So I showed up at the studio, without phoning first, and Miyazaki ignored me,' Suzuki told me. 'He said only one thing: "I'm busy. Go home." I brought over a chair and sat down next to him. He said, "What are you doing?" I said, "I'm not going home until you say something to me." I sat there till late at night, until he went home. The next day I went back and sat down in the same place. On the third night he finally spoke to me, to ask for advice. He asked whether there was a specific term for the kind of car chase he was doing. I told him the name. We talked about other things, and after a while he consented to an interview. But then we tried to take a photo. He didn't want a photo. Only from the back. So I got pissed [off]. I ran the shot and I did a little caption for it: "A very rare photo of the back of Hayao Miyazaki's head." That was my revenge. Starting from that day, we've been working together for 25 years, and I have seen him nearly every day.

In 1985 Tokuma Shoten, the publishing company, opened an animation studio, Ghibli; Toshio Suzuki, Isao Takahata and Hayao Miyazaki became its directors. The name was Miyazaki's choice; ghibli is a word that Italian pilots once used to describe a wind blowing from the Sahara. Miyazaki threw himself into the project. 'He would work from 9am to 4.30am,' Suzuki said. 'He didn't take holidays. He changed quite a bit when he turned 50 – he figured maybe he should take off a Sunday now and then. Now he tends to leave at midnight.'

During my visit to the studio, in an upstairs room I saw Miyazaki hanging out with a couple of animators. He had shown the completed Howl's Moving Castle to his wife and the Ghibli staff that day. He was in a relaxed mood, and when I started asking him questions, through a translator, he started answering.

Miyazaki's hair was parted on the side, and a luxuriant hank of it fell over one eye periodically. He wore big oblong glasses, grey trousers, a light-blue short-sleeved shirt and straw-soled sandals with white socks. At first glance he seemed full of suppressed amusement.

Today, Miyazaki announced cheerfully, marked the last time he would watch Howl's Moving Castle. I never watch my films after they've left the studio, because I've lived it and I know exactly where I've made mistakes,' he said. 'I'd have to cringe and hide, just close my eyes: "Oh, right, I remember that mistake, and that one." You don't have to go through that torment over and over.' The remark was punctuated with a giddy, slightly maniacal laugh. Miyazaki cradled the back of his head with his hand. 'I've done things in this movie I wouldn't have done ten years ago,' he said. 'It has a big climax in the middle, and it ends with a resolution. It's old-fashioned storytelling. Romantic.'

The afternoon was warm, and outside the window cicadas made a racket. Miyazaki continued to look twinkly, but none the less began airing a briskly direview of the world. 'I'm not jealous of young people,' he said. 'They're not really free.' I asked him what he meant. 'They're raised on virtual reality. And it's no better in the countryside. In the country kids spend more time staring at DVDs than kids do in the city.' He went on, 'The best thing would be for virtual reality to disappear. I realise that with our animation we are creating virtual things, too. I tell my crew, "Don't watch animation! You're surrounded by enough virtual things already."'

We walked out to the rooftop garden that Goro had designed as a place where staff could rest and recharge. The studio's four small buildings are lovely, and are complete with Miyazakian refinements. In some workspaces where he thought there wasn't enough light or any hint of the outside, he had trompe l'oeil windows painted that depict meadows beneath cerulean skies. From the garden we could hear taiko drums thumping out a dance for a local festival, and see a flamboyant sunset over the old pine trees that remain in this neighbourhood, unlike in so many others around Tokyo. With surprising enthusiasm Miyazaki brought up the subject of environmental apocalypse. 'Our population could suddenly dip and disappear,' he said, flourishing his cigarette. 'I talked to an expert on this recently, and I said, "Tell me the truth." He said with mass consumption continuing as it is we will have less than 50 years. Then it will all be like Venice. I think maybe less, more like 40. I'm hoping I'll live another 30 years. I want to see the sea rise over Tokyo and the NTV tower become an island. I'd like to see Manhattan underwater.'

I asked him if he wanted to live elsewhere – he seemed so bitter about Japan's environmental depredations. 'No,' he said. 'Japan is fine, because they speak Japanese. I like Ireland, though, the countryside there. Dublin has too many yuppies, computer types, but I like the countryside, because it's poorer than England.' He mentioned liking Potsdam, in Germany, and the decrepit castle at Sans Souci. Miyazaki added that he didn't find travel relaxing; he liked walking, since that was the way humans were meant to relax; and he expresses the wish that he 'could walk back and forth to work every day, except that it would take two and a half hours each way,' and then he wouldn't have so much time to work. This remark suddenly seemed to remind him of all the work he had to do, and he turned to leave.

On the train ride back to central Tokyo I thought about how kind and humane Miyazaki's films typically are, and how harsh he had often sounded in person. I decided to admire this dichotomy as an example of what the social critic Antonio Gramsci called 'pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will.' An interviewer once remarked to Miyazaki that his films expressed 'hope for a belief in the goodness of man.' Miyazaki replied that he was, in fact, a pessimist. He then added, 'I don't want to transfer my pessimism on to children. I keep it at bay. I don't believe that adults should impose their vision of the world on children. Children are very much capable of forming their own visions.'